Other materials - IFs: Difference between revisions

Steve Hedden (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Barry Hughes (talk | contribs) m (Small addition of text to Other materials section) |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

|DocumentationCategory=Other materials | |DocumentationCategory=Other materials | ||

}} | }} | ||

Education | This section provides brief summaries of most of the models in IFs beyond the demographic/population, general equilibrium economic model, and partial equilibrium models for energy and agriculture linked to the respective sectors in the economic model.<h1>Education</h1> | ||

The model forecasts gender- and country-specific access, participation and progression rates at levels of formal education starting from elementary through lower and upper secondary to tertiary. The model also forecasts costs and public spending by level of education. Dropout, completion and transition to the next level of schooling are all mapped onto corresponding age cohorts thus allowing the model to project educational attainment for the entire population at any point in time within the analysis horizon. | The model forecasts gender- and country-specific access, participation and progression rates at levels of formal education starting from elementary through lower and upper secondary to tertiary. The model also forecasts costs and public spending by level of education. Dropout, completion and transition to the next level of schooling are all mapped onto corresponding age cohorts thus allowing the model to project educational attainment for the entire population at any point in time within the analysis horizon. | ||

From simple accounting of the grade progressions to complex budget balancing and budget impact algorithm, the model draws upon the extant understanding and standards (e.g., UNESCO's ISCED classification) about national systems of education around the world. One difference between other attempts at projecting educational participation and attainment and that of IFs is the embedding of education within an integrated model in which demographic and economic variables interact with education, in both directions, as the model runs. | From simple accounting of the grade progressions to complex budget balancing and budget impact algorithm, the model draws upon the extant understanding and standards (e.g., UNESCO's ISCED classification) about national systems of education around the world. One difference between other attempts at projecting educational participation and attainment and that of IFs is the embedding of education within an integrated model in which demographic and economic variables interact with education, in both directions, as the model runs. | ||

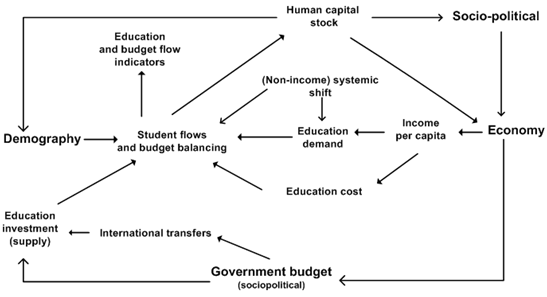

Figure 1 displays the major variables and components that directly determine education demand, supply, and flows in the IFs system. We emphasize again the inter-connectedness of the components and their relationship to the broader human development system. For example, during each year of simulation, the IFs cohort-specific demographic model provides the school age population to the education model. In turn, the education model feeds its calculations of education attainment to the population model’s determination of women’s fertility. Similarly, the broader economic and socio-political systems provide funding for education, and levels of educational attainment affect economic productivity and growth, and therefore also education spending. | [[File:EducationModelinIFs.png]] | ||

Figure 1 (above) displays the major variables and components that directly determine education demand, supply, and flows in the IFs system. We emphasize again the inter-connectedness of the components and their relationship to the broader human development system. For example, during each year of simulation, the IFs cohort-specific demographic model provides the school age population to the education model. In turn, the education model feeds its calculations of education attainment to the population model’s determination of women’s fertility. Similarly, the broader economic and socio-political systems provide funding for education, and levels of educational attainment affect economic productivity and growth, and therefore also education spending. | |||

<h1>Governance</h1> | |||

Governance is the two-way interaction between government and the broader socio-political or, even more broadly, socio-cultural system. The conceptual foundation for the representation of governance in IFs owes much to an analysis of the evolution of governance in countries around the world over several centuries. That analysis (see Chapter 1 of the Strengthening Governance Globally volume by Hughes et al. 2014) identified three dimensions of governance: security, capacity, and inclusion. It traced them over time and noted their largely sequential unfolding for currently developed countries and their currently more nearly simultaneous progression in many lower-income countries. | |||

The three dimensions interact closely and bi-directionally with each other. They also interact bi-directionally with broader human development systems. The level of well-being, often captured quantitatively by GDP per capita or the more inclusive human development index, may be especially important, but is hardly alone in helping drive forward advance in governance; for instance, the age structures of populations and economic structures also interact with governance patterns. | |||

The conceptualization of governance further divides each of the three primary dimensions into two sub-dimensions partly based on the desire to quantify them historically and to facilitate scenario analysis. For security those are the probability of intrastate conflict and the general level of country performance and risk. The two sub-dimensions of capacity are the ability to raise revenue and the effective use of it and the other tools of government—that is, the competence or quality of governance. IFs uses corruption (that is, control of it) as a proxy for such competence. The first sub-dimension of inclusion is the level of formal democratization, typically assessed in terms of competitive elections. More broadly democratization involves inclusion of population groupings across lines such as ethnicity, religion, sex, and age; IFs uses gender equity as a proxy for the second dimension. | |||

<h1>Health</h1> | |||

Health analysis systems typically can help us either (1) to understand better where broad, long-term patterns of human development appear to be taking us with respect to global health, or (2) to consider opportunities for intervention and achievement of alternative health futures, enhancing the foundation for decisions and actions that improve health. | |||

Broad structural models with deep distal drivers such as technological and income advance (e.g., that of the Global Burden of Disease or GBD) assist in the first purpose by relating those distal development drivers to longer-term pattern change in health. Distal driver formulations tend to produce forecasts of constantly decreasing death rates. Yet we know, for instance, that some more proximate factors driving mortality, such as smoking, obesity, and road traffic accidents, tend to increase in developing societies with income and education, before at least smoking and road traffic deaths (and perhaps also obesity) typically decline. The inclusion of such proximate drivers thus opens the door to the second, allowing for consideration of interventions in the pursuit of alternate health futures. A hybrid and integrated model form like that of IFs can help with both purposes and provide a richer overall picture of alternative health futures. | |||

The integrated nature of the IFs modeling system further allows us to think about feedback loops between health outcomes and larger development variables such as economic progress and population structure. | |||

<h1>Infrastructure</h1> | |||

The dominant relations in the Infrastructure model are those that determine the expected levels of infrastructure stocks and access, spending on infrastructure, and the impacts of infrastructure on health and productivity. The expected levels of infrastructure stocks and access are influenced by socio-economic factors related to population, economic activity, governance, and educational attainment—and, of course, spending on construction and maintenance. In almost every case there are also path dependencies that supplement the basic relationships, reflecting the considerable inertia in infrastructure development. | |||

Spending on infrastructure is divided into private and public spending, with the latter further divided in IFs into ‘core’ and ‘other’ infrastructure. ‘Core’ infrastructure refers to those types of infrastructure that are explicitly represented in the model; ‘other’ infrastructure refers to those types of infrastructure that are not explicitly represented in the model. In IFs, public spending on core infrastructure is driven by the required spending to meet the expected levels of infrastructure stocks and access, constrained by total government consumption and the demands for government consumption in other categories (e.g. education and health). Public spending on other infrastructure is driven by average GDP per capita, total government consumption, and the demands on government consumption from other categories. Deficits and surpluses of government funds will affect the actual levels of funds allocated for both core and other infrastructure. The public spending on core infrastructure leverages a proportionate amount of private spending on core infrastructure, with the amount leveraged depending upon historical relationships found in the literature, which normally reflect the variation in public and private returns between particular types of infrastructure. Finally, in recognition of the incremental approaches that public budgeting decisions usually follow, IFs avoids unusually sharp increases in public spending on infrastructure by smoothing it over time. | |||

Infrastructure development directly affects multifactor productivity, with this effect being treated separately for non-ICT and ICT related infrastructure. The use of solid fuels in the home and access to improved water and sanitation directly affect human health through their effects on the mortality and morbidity rates of specific diseases—diarrheal diseases, acute respiratory infections, and respiratory diseases. | |||

<h1>Interstate Politics</h1> | |||

Threat of conflict among sates states is a function of many determinants. For instance, contiguity or physical proximity creates contact and therefore the potential for both threat and peaceful interaction. Cultural similarities and differences affect threat levels. Yet certain factors are more subject to rapid change over time than are contiguity or culture. Among factors that change, the relative power of states and their level of democratization substantially affect levels of conflict threat. | |||

Power is a function of population, GDP, technology, and conventional and nuclear military expenditures, in an aggregation with weights that the user can change. IFs computes a power indicator that shows each actor’s portion of global power. It does so by weighting each actor’s share of global GDP (at exchange rates or purchasing power parity), population, a measure of technological sophistication (with GDP per capita as a proxy), government size, military spending, conventional power, and nuclear power. Weights of one "1" add the term to the power calculation, and of “0” remove the term from power calculation. | |||

Democratization is computed in the domestic socio-political model. | |||

<h1>Socio-political</h1> | |||

Social and political change occurs on three dimensions (social characteristics or individual life conditions, values, and socio-political institutions/process). Although GDP per capita is strongly correlated with all dimensions of change, it might be more appropriate to conceptualize a syndrome or complex of developmental change than to portray an economically-driven process. | |||

The model computes some key social characteristics/life conditions, including life expectancy and fertility rates in the demographic model, but the user can affect them via multipliers. Literacy rate is an endogenous function of education spending, which the user can influence. Building on such variables, IFs provides aggregated indicators of the physical quality of life and the human development index. | |||

The model computes value or cultural change on three dimensions identified by the global World Values Survey project: traditional versus secular-rational, survival versus self-expression, and modernism versus postmodernism, which the user can affect via additive factors. | |||

With respect to socio-political institutions/process, the model endogenously projects freedom, democracy, autocracy, economic freedom, and the status of women. All can be shifted by the user via multipliers. | |||

The larger socio-political model provides representation and control over government spending on education, health, the military, R&D, infrastructure, foreign aid, and a residual category. Military spending is linked to interstate politics, both as a driver of threat and as a result of action-and-reaction based arms spending. | |||

Latest revision as of 16:36, 22 December 2024

| Corresponding documentation | |

|---|---|

| Previous versions | |

| Model information | |

| Model link | |

| Institution | Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures, University of Denver (Pardee Center), Colorado, USA, https://pardee.du.edu/. |

| Solution concept | |

| Solution method | Dynamic recursive with annual time steps through 2100. |

| Anticipation | Myopic |

This section provides brief summaries of most of the models in IFs beyond the demographic/population, general equilibrium economic model, and partial equilibrium models for energy and agriculture linked to the respective sectors in the economic model.

Education

The model forecasts gender- and country-specific access, participation and progression rates at levels of formal education starting from elementary through lower and upper secondary to tertiary. The model also forecasts costs and public spending by level of education. Dropout, completion and transition to the next level of schooling are all mapped onto corresponding age cohorts thus allowing the model to project educational attainment for the entire population at any point in time within the analysis horizon.

From simple accounting of the grade progressions to complex budget balancing and budget impact algorithm, the model draws upon the extant understanding and standards (e.g., UNESCO's ISCED classification) about national systems of education around the world. One difference between other attempts at projecting educational participation and attainment and that of IFs is the embedding of education within an integrated model in which demographic and economic variables interact with education, in both directions, as the model runs.

Figure 1 (above) displays the major variables and components that directly determine education demand, supply, and flows in the IFs system. We emphasize again the inter-connectedness of the components and their relationship to the broader human development system. For example, during each year of simulation, the IFs cohort-specific demographic model provides the school age population to the education model. In turn, the education model feeds its calculations of education attainment to the population model’s determination of women’s fertility. Similarly, the broader economic and socio-political systems provide funding for education, and levels of educational attainment affect economic productivity and growth, and therefore also education spending.

Governance

Governance is the two-way interaction between government and the broader socio-political or, even more broadly, socio-cultural system. The conceptual foundation for the representation of governance in IFs owes much to an analysis of the evolution of governance in countries around the world over several centuries. That analysis (see Chapter 1 of the Strengthening Governance Globally volume by Hughes et al. 2014) identified three dimensions of governance: security, capacity, and inclusion. It traced them over time and noted their largely sequential unfolding for currently developed countries and their currently more nearly simultaneous progression in many lower-income countries.

The three dimensions interact closely and bi-directionally with each other. They also interact bi-directionally with broader human development systems. The level of well-being, often captured quantitatively by GDP per capita or the more inclusive human development index, may be especially important, but is hardly alone in helping drive forward advance in governance; for instance, the age structures of populations and economic structures also interact with governance patterns.

The conceptualization of governance further divides each of the three primary dimensions into two sub-dimensions partly based on the desire to quantify them historically and to facilitate scenario analysis. For security those are the probability of intrastate conflict and the general level of country performance and risk. The two sub-dimensions of capacity are the ability to raise revenue and the effective use of it and the other tools of government—that is, the competence or quality of governance. IFs uses corruption (that is, control of it) as a proxy for such competence. The first sub-dimension of inclusion is the level of formal democratization, typically assessed in terms of competitive elections. More broadly democratization involves inclusion of population groupings across lines such as ethnicity, religion, sex, and age; IFs uses gender equity as a proxy for the second dimension.

Health

Health analysis systems typically can help us either (1) to understand better where broad, long-term patterns of human development appear to be taking us with respect to global health, or (2) to consider opportunities for intervention and achievement of alternative health futures, enhancing the foundation for decisions and actions that improve health.

Broad structural models with deep distal drivers such as technological and income advance (e.g., that of the Global Burden of Disease or GBD) assist in the first purpose by relating those distal development drivers to longer-term pattern change in health. Distal driver formulations tend to produce forecasts of constantly decreasing death rates. Yet we know, for instance, that some more proximate factors driving mortality, such as smoking, obesity, and road traffic accidents, tend to increase in developing societies with income and education, before at least smoking and road traffic deaths (and perhaps also obesity) typically decline. The inclusion of such proximate drivers thus opens the door to the second, allowing for consideration of interventions in the pursuit of alternate health futures. A hybrid and integrated model form like that of IFs can help with both purposes and provide a richer overall picture of alternative health futures.

The integrated nature of the IFs modeling system further allows us to think about feedback loops between health outcomes and larger development variables such as economic progress and population structure.

Infrastructure

The dominant relations in the Infrastructure model are those that determine the expected levels of infrastructure stocks and access, spending on infrastructure, and the impacts of infrastructure on health and productivity. The expected levels of infrastructure stocks and access are influenced by socio-economic factors related to population, economic activity, governance, and educational attainment—and, of course, spending on construction and maintenance. In almost every case there are also path dependencies that supplement the basic relationships, reflecting the considerable inertia in infrastructure development.

Spending on infrastructure is divided into private and public spending, with the latter further divided in IFs into ‘core’ and ‘other’ infrastructure. ‘Core’ infrastructure refers to those types of infrastructure that are explicitly represented in the model; ‘other’ infrastructure refers to those types of infrastructure that are not explicitly represented in the model. In IFs, public spending on core infrastructure is driven by the required spending to meet the expected levels of infrastructure stocks and access, constrained by total government consumption and the demands for government consumption in other categories (e.g. education and health). Public spending on other infrastructure is driven by average GDP per capita, total government consumption, and the demands on government consumption from other categories. Deficits and surpluses of government funds will affect the actual levels of funds allocated for both core and other infrastructure. The public spending on core infrastructure leverages a proportionate amount of private spending on core infrastructure, with the amount leveraged depending upon historical relationships found in the literature, which normally reflect the variation in public and private returns between particular types of infrastructure. Finally, in recognition of the incremental approaches that public budgeting decisions usually follow, IFs avoids unusually sharp increases in public spending on infrastructure by smoothing it over time.

Infrastructure development directly affects multifactor productivity, with this effect being treated separately for non-ICT and ICT related infrastructure. The use of solid fuels in the home and access to improved water and sanitation directly affect human health through their effects on the mortality and morbidity rates of specific diseases—diarrheal diseases, acute respiratory infections, and respiratory diseases.

Interstate Politics

Threat of conflict among sates states is a function of many determinants. For instance, contiguity or physical proximity creates contact and therefore the potential for both threat and peaceful interaction. Cultural similarities and differences affect threat levels. Yet certain factors are more subject to rapid change over time than are contiguity or culture. Among factors that change, the relative power of states and their level of democratization substantially affect levels of conflict threat.

Power is a function of population, GDP, technology, and conventional and nuclear military expenditures, in an aggregation with weights that the user can change. IFs computes a power indicator that shows each actor’s portion of global power. It does so by weighting each actor’s share of global GDP (at exchange rates or purchasing power parity), population, a measure of technological sophistication (with GDP per capita as a proxy), government size, military spending, conventional power, and nuclear power. Weights of one "1" add the term to the power calculation, and of “0” remove the term from power calculation.

Democratization is computed in the domestic socio-political model.

Socio-political

Social and political change occurs on three dimensions (social characteristics or individual life conditions, values, and socio-political institutions/process). Although GDP per capita is strongly correlated with all dimensions of change, it might be more appropriate to conceptualize a syndrome or complex of developmental change than to portray an economically-driven process.

The model computes some key social characteristics/life conditions, including life expectancy and fertility rates in the demographic model, but the user can affect them via multipliers. Literacy rate is an endogenous function of education spending, which the user can influence. Building on such variables, IFs provides aggregated indicators of the physical quality of life and the human development index.

The model computes value or cultural change on three dimensions identified by the global World Values Survey project: traditional versus secular-rational, survival versus self-expression, and modernism versus postmodernism, which the user can affect via additive factors.

With respect to socio-political institutions/process, the model endogenously projects freedom, democracy, autocracy, economic freedom, and the status of women. All can be shifted by the user via multipliers.

The larger socio-political model provides representation and control over government spending on education, health, the military, R&D, infrastructure, foreign aid, and a residual category. Military spending is linked to interstate politics, both as a driver of threat and as a result of action-and-reaction based arms spending.