Energy resource endowments - IMAGE: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (Text replacement - "|QQQ " to "") |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ModelDocumentationTemplate | {{ModelDocumentationTemplate | ||

|IsEmpty=No | |||

|IsDocumentationOf=IMAGE | |IsDocumentationOf=IMAGE | ||

|DocumentationCategory=Energy resource endowments | |DocumentationCategory=Energy resource endowments | ||

}} | }} | ||

__FORCETOC__ | |||

==Introduction== | |||

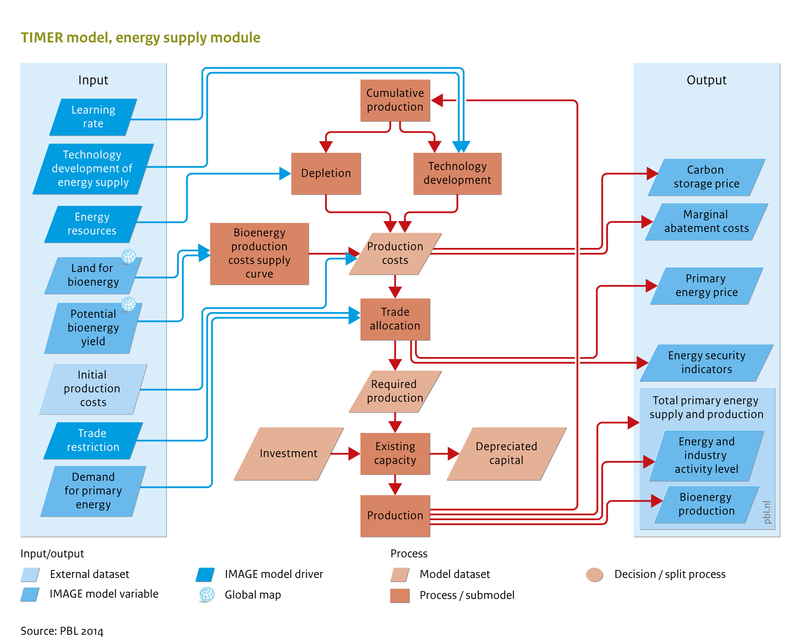

A key factor in future energy supply is the availability (and depletion) of various resources. One aspect is that energy resources are unevenly spread across world regions and often, poorly matched with regional energy demand. This is directly related to energy security. In representation of energy supply, the IMAGE energy model, describes long-term dynamics based on the interplay between resource depletion (upward pressure on prices) and technology development (downward pressure on prices). In the model, technology development is introduced in the form of learning curves for most fuels and renewable options. Costs decrease endogenously as a function of the cumulative energy capacity, and in some cases, assumptions are made about exogenous technology change. | |||

Depletion is a function of either cumulative production or annual production. For example, for fossil-fuel resources and nuclear feedstock, low-cost resources are slowly being depleted, and thus higher cost resources need to be used. In annual production, for example, of renewables, attractive production sites are used first. Higher annual production levels require use of less attractive sites with less wind or lower yields. | |||

It is assumed that all demand is always met. Because regions are usually unable to meet all of their own demand, energy carriers, such as coal, oil and gas, are widely traded. The impact of depletion and technology development lead to changes in primary fuel prices, which influence investment decisions in the end-use and energy-conversion modules Linkages to other parts of IMAGE framework include available land for bioenergy production, emissions of greenhouse gases and air pollutants (partly related to supply), and the use of land for bioenergy production (land use for other energy forms are not taken into account). Several key assumptions determine the long-term behaviour of the various energy supply submodules and are mostly related to technology development and resource base. | |||

An overview of the general energy supply model structure is provided in <xr id="fig:EnergySupply"></xr>. | |||

<figure id="fig:EnergySupply"> | |||

[[File:EnergySupply.png|800px|thumb|left|<caption>Flowchart Energy supply.</caption>]] | |||

</figure> | |||

<div style="clear:left"></div> | |||

==Fossil fuels, uranium and fissile resources== | ==Fossil fuels, uranium and fissile resources== | ||

Depletion of fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) and uranium is simulated on the assumption that resources can be represented by a long-term supply cost curve, consisting of different resource categories with increasing cost levels. The model assumes that the cheapest deposits will be exploited first taking into account trade costs between regions. For each region, there are 12 resource categories for oil, gas and nuclear fuels, and 14 categories for coal. A key input for each of the fossil fuel and uranium supply submodules is fuel demand (fuel used in final energy and conversion processes). Additional input includes conversion losses in refining, liquefaction, conversion, and energy use in the energy system . These submodules indicate how demand can be met by supply in a region and other regions through interregional trade. | Depletion of fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) and uranium is simulated on the assumption that resources can be represented by a long-term supply cost curve, consisting of different resource categories with increasing cost levels. The model assumes that the cheapest deposits will be exploited first taking into account trade costs between regions. For each region, there are 12 resource categories for oil, gas and nuclear fuels, and 14 categories for coal. A key input for each of the fossil fuel and uranium supply submodules is fuel demand (fuel used in final energy and conversion processes). Additional input includes conversion losses in refining, liquefaction, conversion, and energy use in the energy system. These submodules indicate how demand can be met by supply in a region and other regions through interregional trade. | ||

<figtable id="tab:IMAGE_1"> | <figtable id="tab:IMAGE_1"> | ||

| Line 56: | Line 69: | ||

==Bioenergy== | ==Bioenergy== | ||

Supply of biomass and bioenergy is based on the availability of two resources: Energy crops, and residues. Thier supply is determined as follows: | |||

* Energy crops[[CiteRef::CiteRef::IMG_Daioglou_2019]]: | |||

** Primary energy crops are: Sugar-cane, maize, oil-crops, woody, and grassy crops. | |||

** Thier potential follows similar rules as those of fossil fuels but with some small differences. Depletion of energy crops is not governed by cumulative production but by the degree to which available land is used for commercial energy crops. | |||

** The total amount of potentially available bioenergy is derived from energy crop yields calculated on a 0.5x0.5 degree grid with the IMAGE crop model for various land-use scenarios for the 21st century. Potential supply is restricted on the basis of a set of criteria, the most important of which is that energy crops can only be on abandoned agricultural land and on part of the natural grassland. | |||

** The costs of primary energy crops are calculated with a Cobb-Douglas production function using labour , land rent and capital costs as inputs. The land costs are based on average regional income levels per km2, which was found to be a reasonable proxy for regional differences in land rent costs. The production functions are calibrated to empirical data [[CiteRef::IMG_Hoogwijk_2004]]. | |||

* Residues[[CiteRef::CiteRef::IMG_Daioglou_2016]]: | |||

** These are a byproduct of agricultural and forestry production. These are calculated on a 0.5x0.5 degree grid based on scenario projections. | |||

** Theoretical potential is based on agricultural yields and crop types (agricultural residues), and forest type and management (forestry residues) | |||

** A certain portion of the theoretical potential has to remain on the land to maintain nvironmental functions. This results in the environmental potential. | |||

** furthermore, some residues are diverted for (i) fuel use in poor households, and (ii) Livestock feed. The volume diverted depends on the scenario projection | |||

** This results in an available potential. | |||

** Spatially explicit costs are based on the yield of available potential, labour costs, and overheads. | |||

The production costs for bioenergy are represented by the costs of feedstock and conversion. Feedstock costs increase with actual production as a result of depletion, while conversion costs decrease with cumulative production as a result of ''learning by doing''. Feedstock costs include the costs of land, labour and capital, while conversion costs include capital, O&M and energy use in this process. For both steps, the associated greenhouse gas emissions (related to deforestation, N2O from fertilisers, energy) are estimated, and are subject to carbon tax, where relevant. | The model describes the conversion of biomass (energy crops and residues) to two generic secondary fuel types: bio-solid fuels used in the industry and power sectors; and liquid fuel used in the transport, residential, and chemical sectors[[CiteRef::CiteRef::IMG_Daioglou_2019]]. The trade and allocation of biofuel production to regions is determined by optimisation. An optimal mix of bio-solid and bio-liquid fuel supply across regions is calculated, using the prices of the previous time step to calculate the demand. The production costs for bioenergy are represented by the costs of feedstock and conversion. Feedstock costs increase with actual production as a result of depletion, while conversion costs decrease with cumulative production as a result of ''learning by doing''. Feedstock costs include the costs of land, labour and capital, while conversion costs include capital, O&M and energy use in this process. For both steps, the associated greenhouse gas emissions (related to deforestation, N2O from fertilisers, energy) are estimated[[CiteRef::CiteRef::IMG_Daioglou_2017]], and are subject to carbon tax, where relevant. | ||

==Wind and solar energy== | ==Wind and solar energy== | ||

Latest revision as of 17:13, 23 June 2020

| Corresponding documentation | |

|---|---|

| Previous versions | |

| Model information | |

| Model link | |

| Institution | PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL), Netherlands, https://www.pbl.nl/en. |

| Solution concept | Partial equilibrium (price elastic demand) |

| Solution method | Simulation |

| Anticipation | Simulation modelling framework, without foresight. However, a simplified version of the energy/climate part of the model (called FAIR) can be run prior to running the framework to obtain data for climate policy simulations. |

Introduction

A key factor in future energy supply is the availability (and depletion) of various resources. One aspect is that energy resources are unevenly spread across world regions and often, poorly matched with regional energy demand. This is directly related to energy security. In representation of energy supply, the IMAGE energy model, describes long-term dynamics based on the interplay between resource depletion (upward pressure on prices) and technology development (downward pressure on prices). In the model, technology development is introduced in the form of learning curves for most fuels and renewable options. Costs decrease endogenously as a function of the cumulative energy capacity, and in some cases, assumptions are made about exogenous technology change.

Depletion is a function of either cumulative production or annual production. For example, for fossil-fuel resources and nuclear feedstock, low-cost resources are slowly being depleted, and thus higher cost resources need to be used. In annual production, for example, of renewables, attractive production sites are used first. Higher annual production levels require use of less attractive sites with less wind or lower yields.

It is assumed that all demand is always met. Because regions are usually unable to meet all of their own demand, energy carriers, such as coal, oil and gas, are widely traded. The impact of depletion and technology development lead to changes in primary fuel prices, which influence investment decisions in the end-use and energy-conversion modules Linkages to other parts of IMAGE framework include available land for bioenergy production, emissions of greenhouse gases and air pollutants (partly related to supply), and the use of land for bioenergy production (land use for other energy forms are not taken into account). Several key assumptions determine the long-term behaviour of the various energy supply submodules and are mostly related to technology development and resource base. An overview of the general energy supply model structure is provided in <xr id="fig:EnergySupply"></xr>.

<figure id="fig:EnergySupply">

</figure>

Fossil fuels, uranium and fissile resources

Depletion of fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) and uranium is simulated on the assumption that resources can be represented by a long-term supply cost curve, consisting of different resource categories with increasing cost levels. The model assumes that the cheapest deposits will be exploited first taking into account trade costs between regions. For each region, there are 12 resource categories for oil, gas and nuclear fuels, and 14 categories for coal. A key input for each of the fossil fuel and uranium supply submodules is fuel demand (fuel used in final energy and conversion processes). Additional input includes conversion losses in refining, liquefaction, conversion, and energy use in the energy system. These submodules indicate how demand can be met by supply in a region and other regions through interregional trade.

<figtable id="tab:IMAGE_1">

| Oil | Natural gas | Underground coal | Surface coal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cum. 1970-2005 production | 4.4 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.1 |

| Reserves | 4.8 | 4.6 | 23.0 | 2.2 |

| Other conventional resources | 6.6 | 6.9 | 117.7 | 10.0 |

| Unconventional resources (reserves) | 46.2 | 498.6 | 1.3 | 23.0 |

| Total | 65 | 519.2 | 168.6 | 270.0 |

</figtable>

Fossil fuel resources are aggregated to five resource categories for each fuel (see table above). Each category has typical production costs. The resource estimates for oil and natural gas imply that for conventional resources supply is limited to only two to eight times the 1970--2005 production level. Production estimates for unconventional resources are much larger, albeit very speculative. Recently, some of the occurrences of these unconventional resources have become competitive such as shale gas and tar sands. For coal, even current reserves amount to almost ten times the production level of the last three decades. For all fuels, the model assumes that, if prices increase, or if there is further technology development, the energy could be produced in the higher cost resource categories. The values presented in the table above represent medium estimates in the model, which can also use higher or lower estimates in the scenarios. The final production costs in each region are determined by the combined effect of resource depletion and learning-by-doing.

Bioenergy

Supply of biomass and bioenergy is based on the availability of two resources: Energy crops, and residues. Thier supply is determined as follows:

- Energy cropsIMG_Daioglou_2019:

- Primary energy crops are: Sugar-cane, maize, oil-crops, woody, and grassy crops.

- Thier potential follows similar rules as those of fossil fuels but with some small differences. Depletion of energy crops is not governed by cumulative production but by the degree to which available land is used for commercial energy crops.

- The total amount of potentially available bioenergy is derived from energy crop yields calculated on a 0.5x0.5 degree grid with the IMAGE crop model for various land-use scenarios for the 21st century. Potential supply is restricted on the basis of a set of criteria, the most important of which is that energy crops can only be on abandoned agricultural land and on part of the natural grassland.

- The costs of primary energy crops are calculated with a Cobb-Douglas production function using labour , land rent and capital costs as inputs. The land costs are based on average regional income levels per km2, which was found to be a reasonable proxy for regional differences in land rent costs. The production functions are calibrated to empirical data IMG_Hoogwijk_2004.

- ResiduesIMG_Daioglou_2016:

- These are a byproduct of agricultural and forestry production. These are calculated on a 0.5x0.5 degree grid based on scenario projections.

- Theoretical potential is based on agricultural yields and crop types (agricultural residues), and forest type and management (forestry residues)

- A certain portion of the theoretical potential has to remain on the land to maintain nvironmental functions. This results in the environmental potential.

- furthermore, some residues are diverted for (i) fuel use in poor households, and (ii) Livestock feed. The volume diverted depends on the scenario projection

- This results in an available potential.

- Spatially explicit costs are based on the yield of available potential, labour costs, and overheads.

The model describes the conversion of biomass (energy crops and residues) to two generic secondary fuel types: bio-solid fuels used in the industry and power sectors; and liquid fuel used in the transport, residential, and chemical sectorsIMG_Daioglou_2019. The trade and allocation of biofuel production to regions is determined by optimisation. An optimal mix of bio-solid and bio-liquid fuel supply across regions is calculated, using the prices of the previous time step to calculate the demand. The production costs for bioenergy are represented by the costs of feedstock and conversion. Feedstock costs increase with actual production as a result of depletion, while conversion costs decrease with cumulative production as a result of learning by doing. Feedstock costs include the costs of land, labour and capital, while conversion costs include capital, O&M and energy use in this process. For both steps, the associated greenhouse gas emissions (related to deforestation, N2O from fertilisers, energy) are estimatedIMG_Daioglou_2017, and are subject to carbon tax, where relevant.

Wind and solar energy

Potential supply of renewable energy (wind, solar and bioenergy) is estimated generically as follows IMG_Hoogwijk_2004IMG_DeVries_2007:

- Physical and geographical data for the regions considered are collected on a 0.5x0.5 degree grid. The characteristics of wind speed, insulation and monthly variation are taken from the digital database constructed by the Climate Research Unit IMG_New_1997.

- The model assesses the part of the grid cell that can be used for energy production, given its physical--geographic (terrain, habitation) and socio-geographical (location, acceptability) characteristics. This leads to an estimate of the geographical potential. Several of these factors are scenario-dependent. The geographical potential for biomass production from energy crops is estimated using suitability/ availability factors taking account of competing land-use options and the harvested rain-fed yield of energy crops.

- Next, we assume that only part of the geographical potential can be used due to limited conversion efficiency and maximum power density, This result of accounting for these conversion efficiencies is referred to as the technical potential.

- The final step is to relate the technical potential to on-site production costs. Information at grid level is sorted and used as supply cost curves to reflect the assumption that the lowest cost locations are exploited first. Supply cost curves are used dynamically and change over time as a result of the learning effect.